The very “One Water” way to manage water resources on developments in the Wimberley Valley

1. INTRODUCTION

Imagine a water management strategy that would accommodate growth and development without unsustainably pumping down aquifers or incurring the huge expense and societal disruption to build reservoirs or transport water from remote supplies to developing areas. Welcome to the concept of Zero Net Water. As the name implies, it is a management concept that would result in zero net demand on our conventional water supplies. Well, practically speaking, approaching zero, as will be reviewed below.

The Zero Net Water concept combines 3 components:

- Building-scale Rainwater Harvesting (RWH), the basis of water supply

- The Decentralized Concept of Wastewater Management, focusing on reusing the wastewater; the hard-won rainwater supply, after being used once in the building, is reused to provide irrigation water supply.

- The Low-Impact Development (LID) stormwater management strategy, employed to maintain the hydrologic integrity of the land, and so of the watershed, as it is developed.

An indication of the potential of building-scale rainwater harvesting as a water supply in the Wimberley Valley is offered by this simple calculation. In one recent year, total water supply that the Wimberley Water Supply Corporation produced was about 154 MILLION gallons. The lowest annual rainfall recorded in Austin during the 1950s drought of record was 11.55 inches. With that rainfall, over the 20 square mile Wimberley WSC service area, the amount of water falling on that area would be a little over 4 BILLION gallons, so annual water usage would be about 4% of the rain falling on the area. At the average annual rainfall in Wimberley of 32.87 inches, the amount of water falling on the service area would be over 11 BILLION gallons. With that rainfall, the usage would be only about 1.5% of the water falling on this area. Clearly, there is far more water falling than could be used, even in a year of very low rainfall.

Of course, only a very minor fraction of the total area could be covered with suitable collection surfaces. And no one is suggesting that all other water supplies be abandoned, to rely only on building-scale rainwater harvesting. This just shows that the ability is there to significantly augment those supplies to serve growth. In the next section, it will be reviewed just how much this practice could off-load the conventional supply sources at each building.

But as noted Zero Net Water is not just building-scale rainwater harvesting – it is an integrated strategy, that creates greater overall water use efficiency. Water supply is integrated with wastewater management by centering the latter on decentralized reclamation and reuse, mainly for irrigation supply. Water supply would also integrate with stormwater management by using Low-Impact Development, green infrastructure and volume-based hydrology methods, to hold water on the land, maintaining hydrologic integrity of the watershed as it is developed, and reducing the area of landscaping that might need to be irrigated.

This integrated management results in minimal disruption of flows through the watershed, even as water is harvested at the site scale to be used – and reused – there to support development, creating a sustainable water development model. This integrated model would better utilize the water supply that routinely falls upon the Wimberley Valley, so rendering the whole system more efficient. This all is of course the essence of the “One Water” idea.

2. RAINWATER HARVESTING FOR WATER SUPPLY

Using building-scale rainwater harvesting for water supply instead of conventional sources can actually increase the overall efficiency of the water system. This is accomplished by taking advantage of the inherent difference in capture efficiency between building-scale and watershed-scale rainwater harvesting. Of course, all our conventional water supplies are watershed-scale rainwater harvesting systems. Which are inherently inefficient.

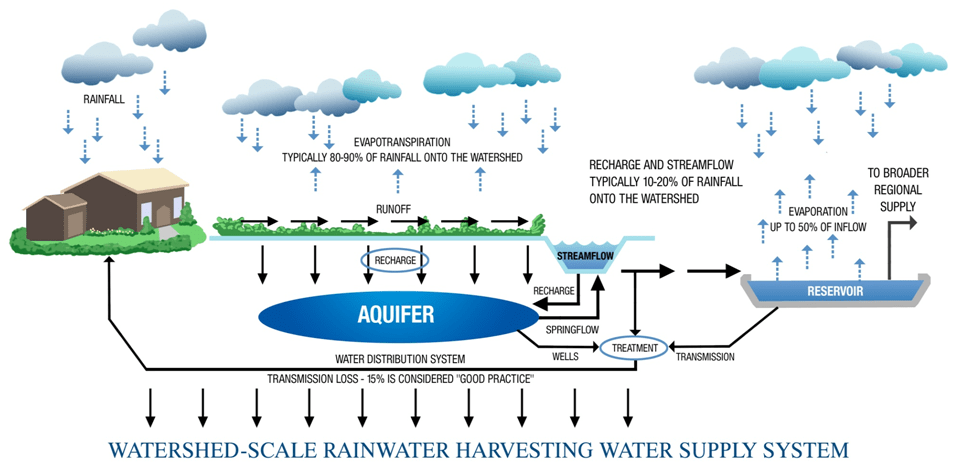

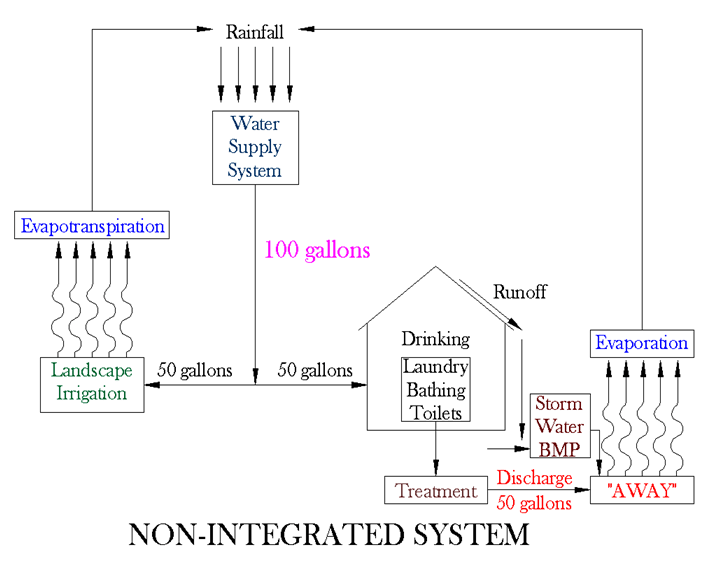

A really big inefficiency, as can be seen in the illustration in Figure 1, is that only a minor fraction of rainfall over a watershed, something like 15%, makes it into streams, reservoirs or aquifers, the “cisterns” of the watershed-scale system. Most of it is lost to evapotranspiration, which of course supports plant life in the watershed.

What does get into reservoirs is subject to very high evaporation loss. To offer a quantitative feel for how big a loss this is, evaporative loss each year from the Highland Lakes is more water than Austin treats and uses annually.

Then the water from those cisterns must be distributed back to where it is to be used, losing more water. Industry standards say 15% transmission loss is “good practice”, and many distribution systems have much higher losses. The Aqua system serving Woodcreek, for example, has reported a loss rate up around 30%.

There are also what might be called “quality inefficiencies”. Water collected in reservoirs is somewhat impaired relative to the quality of rainfall, and needs considerable treatment. And even though it is generally considered potable, water in aquifers can be hard, or contain things like sulfur or iron, and also need some treatment. Treatment imparts costs and consumes energy.

There certainly is a high energy cost. Besides treatment, it takes a lot to lift water out of aquifers, to pump it long distances, and to pressurize the far-flung distribution system.

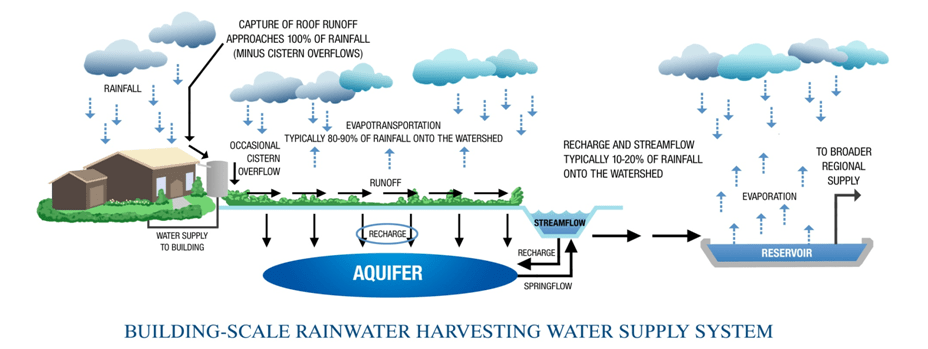

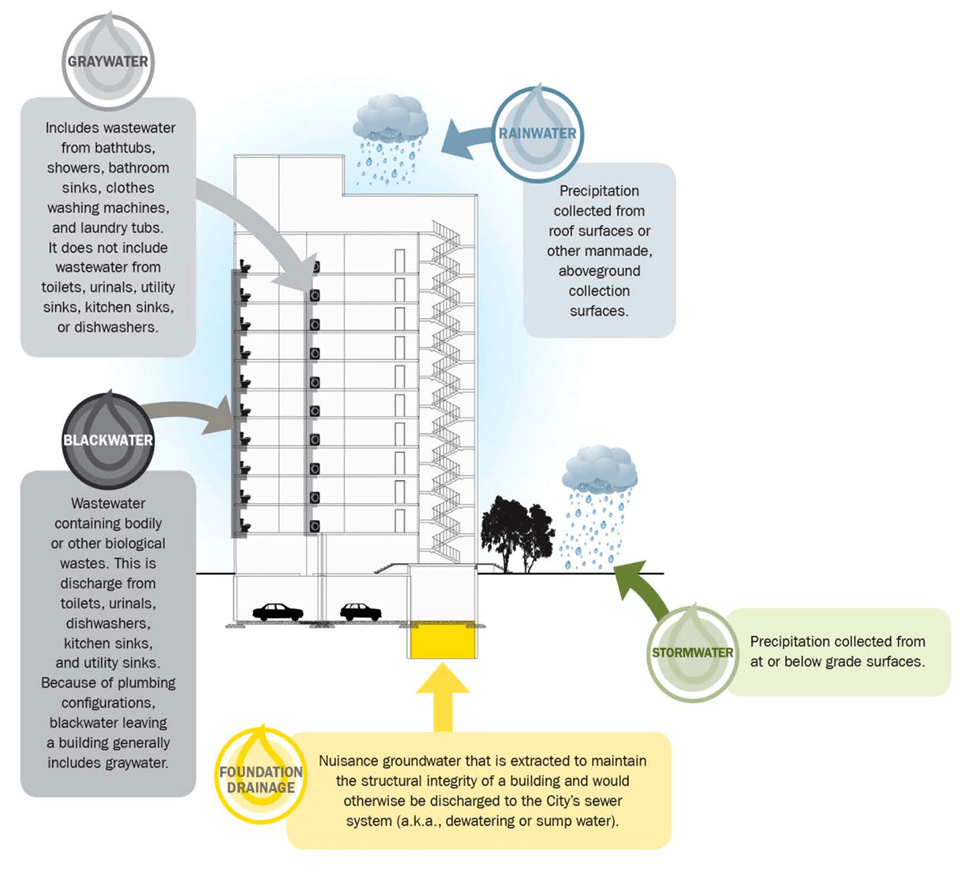

The building-scale rainwater harvesting system, illustrated in Figure 2, blunts all those inefficiencies. The inherent capture efficiency off a rooftop into a cistern approaches 100%. The actual efficiency will be less, of course, due to cistern overflows, wind conditions, gutter overflows during intense rainfalls, and so on, but still it will be very high.

Since the cisterns are covered vessels, there will be negligible evaporation loss. The building-scale distribution system is “short”, largely within the building, but in any case is built, and can realistically be maintained, “tight”, so transmission loss is also negligible.

Rainwater captured directly off a roof is very lightly impaired, so doesn’t need much treatment – cartridge filtration and UV disinfection is the typical system – so a lot of energy is being saved there. With a low lift out of the cistern and a very short run to where the water is used, the building-scale system uses far less energy to move water to the point of use. Given the water-energy nexus – it can take a lot of water to make energy – this also renders the overall system more efficient.

Growth dynamics make the building-scale system economically efficient. Since this system is installed one building at a time, it “grows” the water supply in direct proportion with demand. So besides more efficiently transforming rainfall into a supply usable by humans, creating a more sustainable water supply system, this strategy also creates a more economically sustainable system, because supply is built, and paid for, only in response to imminent demand, one building at a time.

So it can reasonably be asked, which of these models is more sane? Collect high quality water, very efficiently, where it falls and use it there? OR collect it at very low efficiency, with impaired quality, over the whole watershed, then lose a bunch – and use a lot of energy – running it through a long loop … back to where the water fell to begin with? The building-scale system is the clear winner on this question.

3. THE LOW-IMPACT DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

Before going on, a myth about this strategy must be addressed. Some say harvesting off all the roofs would rob streamflow, that it wouldn’t more efficiently harvest water, it would just rob some from downstream users who depend on that flow. But if we examine that premise …

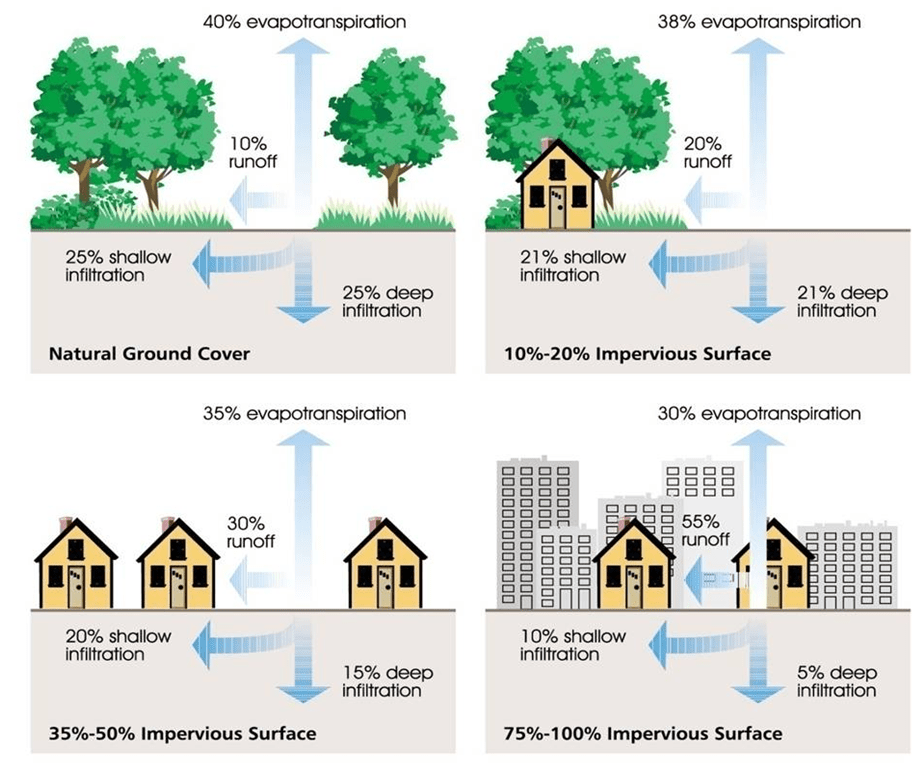

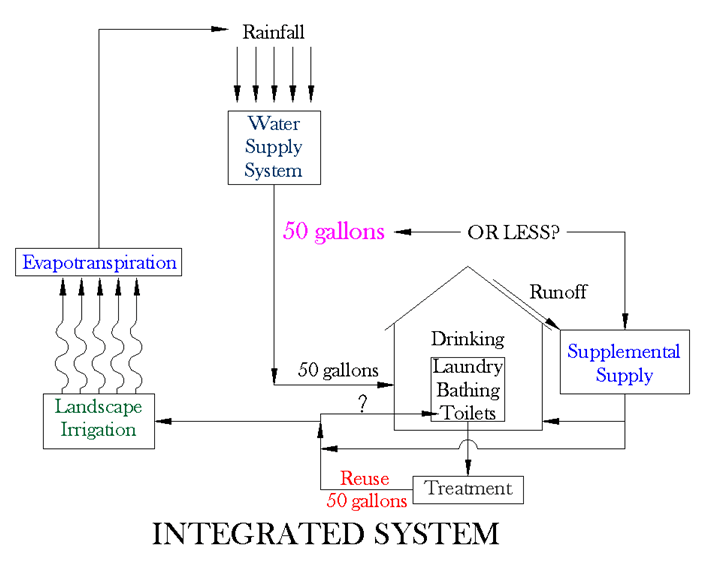

The Zero Net Water strategy would be used to serve new development, and when raw land is developed, as illustrated in Figure 3 quickflow runoff increases at the expense of decreased infiltration. When the land is transformed from a natural site to just 10-20% impervious cover, like in an exurban subdivision, the runoff would double, and with housing at more like urban intensity, typically imparting 35-50% impervious cover, it would triple. To prevent flooding, water quality, and channel erosion problems, measures must be taken to mitigate that shift from infiltration to runoff.

Development rules in this area typically require that runoff be captured and treated, to protect water quality and minimize channel erosion. Unfortunately, much of mainstream practice centers on large end-of-pipe devices, like sand filters, which largely pass the water through, letting it flow away rather than holding it on the land.

This is where the Low-Impact Development stormwater runoff management strategy comes into play, to mitigate that problem. LID practices like the bioretention bed illustrated in Figure 4. Bioretention beds can retain and infiltrate a large portion of the total annual rainfall, shifting the balance back toward infiltration. Instead of a bare sand filter, this is site beautification, designed into the development plan, instead of just appended on, as those sandboxes are. It is also landscaping that doesn’t need routine irrigation, saving some water there.

An even better strategy is to scale these bioretention beds down and spread them around. At this scale, as shown in Figure 5, these installations are usually called by their more colloquial name, “rain gardens”. With this strategy, the rainfall is captured and infiltrated in a manner that more closely mimics how that is done on the native site, on a highly distributed basis. Using many distributed rain gardens instead of one end-of-pipe pond somewhat restores the “hydrologic roughness” which is characteristic of raw land, so holding water on the land. This maximizes hydrologic integrity, achieving that aspect of Zero Net Water. And again, creates interesting landscape elements that don’t need routine irrigation.

Back to the myth, if building-scale rainwater harvesting is integrated into that capture process, harvesting runoff from the rooftop portion of new impervious cover, this just further mitigates the negative hydrologic changes that development causes. Because development causes such large increases in runoff, despite rainwater harvesting off rooftops, runoff from the developed site typically increases over what runs off the native site, even with the LID strategy being applied.

And then too, water collected in the cistern does not exit the watershed. No one is putting it in a truck and hauling it away. It is just being held up for awhile, then rejoins the hydrologic cycle in the vicinity where the rain fell to begin with. Most of the water collected for interior use eventually appears as wastewater. Under Zero Net Water, that’s used for irrigation, so the water that was harvested, after being used once in the building, is still maintaining plant cover in the watershed.

The bottom line is that some of that additional runoff created by development is captured and utilized. That is done instead of allowing the additional runoff to become quickflow, which if not mitigated in some other way creates water quality, channel erosion and flooding problems. Thus, with building-scale rainwater harvesting, overall yield of water supply usable by humans can be fundamentally improved, increasing the usable water yield without any significant impact on streamflow.

4. THE CAVEAT TO “ZERO”, CREATING PRACTICAL RAINWATER HARVESTING BUILDINGS

The building-scale cistern operates just like a reservoir, holding water for future use; indeed, it is a “distributed reservoir”. So like any reservoir, it will produce a “firm yield” of water supply, that will cover a certain amount of demand.

As will be reviewed shortly, considerations of cost efficiency lead to the concept of “right-sizing” the building-scale system – its roofprint and cistern capacity – so, that “firm yield” would cover demands most of the time. Instead of spending a lot more upsizing the system to cover the lastlittle bit of demand in a drought, a backup supply would be brought in to cover that. When, and only when, conditions do get bad enough that it would be needed.

Of course, that backup supply would come from the watershed-scale system, which would itself be most stressed just when that backup supply is needed. So it must be considered, what impact would that have on the watershed-scale system?

The total market for development is set by a whole lot of factors other than, “Is there a water supply available?” So it can be presumed that whatever development is served by building-scale rainwater harvesting would not be additional development, it would just displace some of the development that would otherwise have drawn from the watershed-scale system. Indeed, the point of Zero Net Water is to off-load the watershed-scale system, to avoid costly expansions of that system, like the long pipelines from far-away aquifers that have been proposed to be run into the Wimberley Valley. And also to avoid depleting aquifers and drying up springs, like might be imparted in the Wimberley Valley by development continuing to rely on local groundwater.

Therefore building-scale RWH systems would be “right-sized” to off-load the watershed-scale system most of the time, allowing it to retain that supply, so it could provide a small percentage of total building-scale system demand through a drought. And then, when the rains do come, the watershed-scale system would also recover faster, because the draw on it for backup supply of the building-scale systems would stop, again off-loading the watershed-scale system.

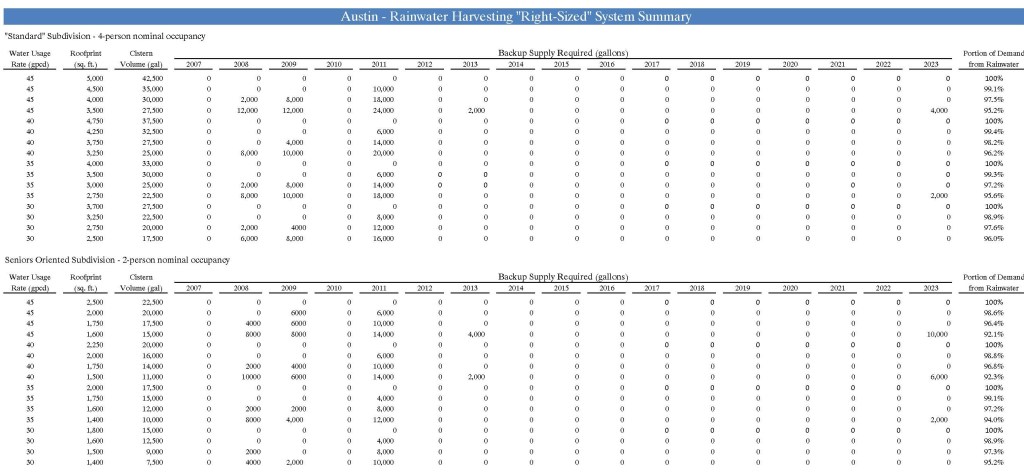

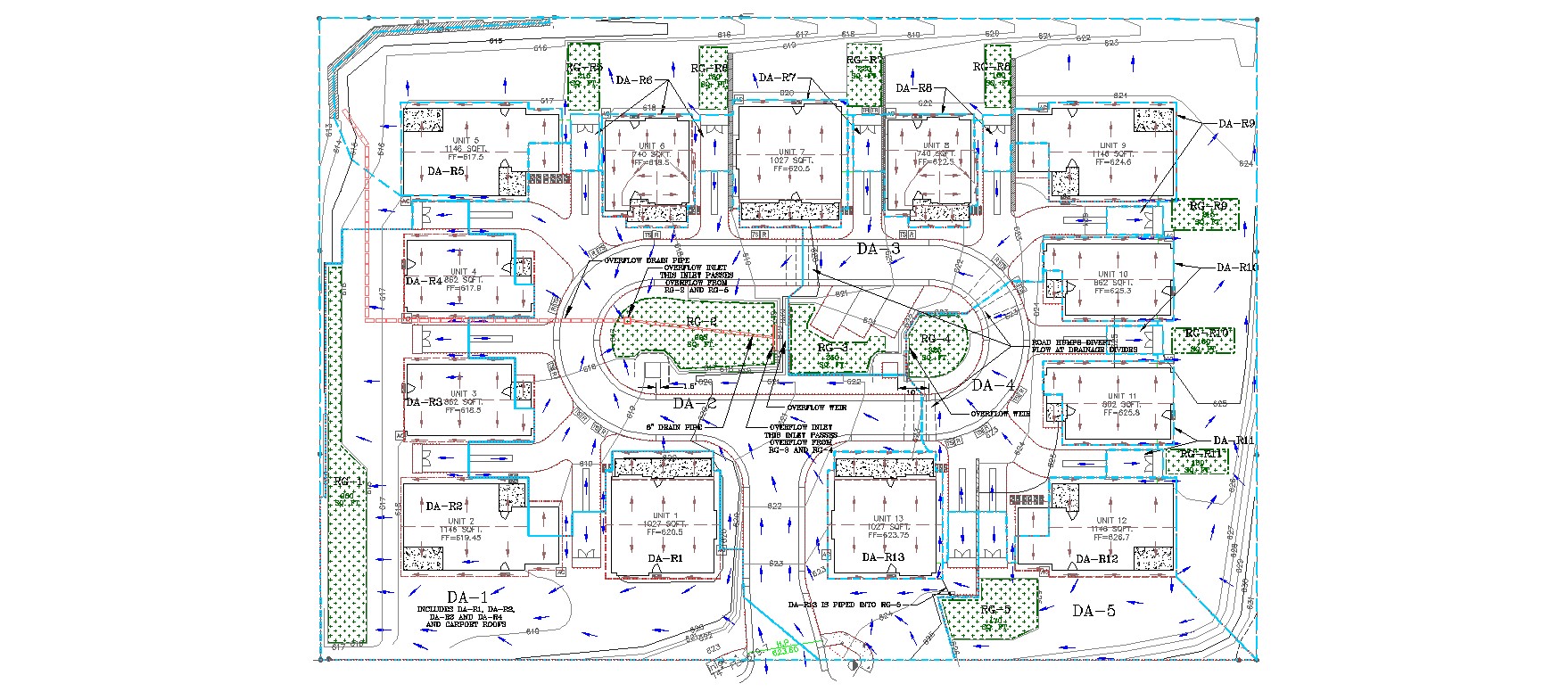

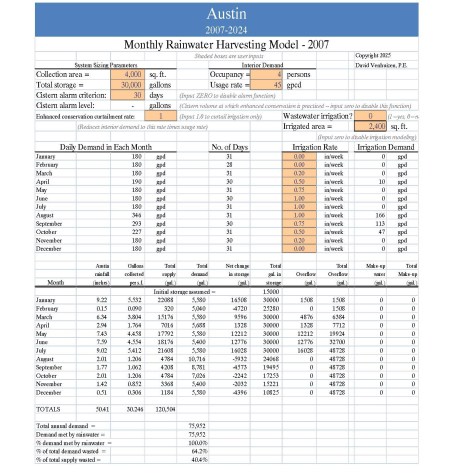

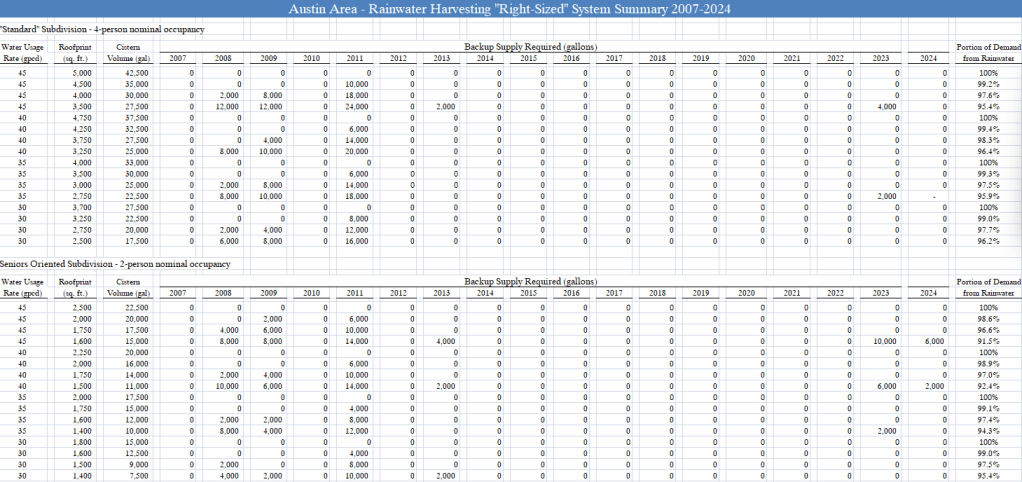

A historical rainfall model is used to determine what would be a “right-sized” system. Here a model using rainfall data for the Austin area covering the years 2007 to 2024 is used to illustrate that. This covers the 2008-2014 drought period, now recognized as the new drought of record for the Highland Lakes, and the more recent somewhat dry years, so this period presents a fairly severe scenario for the sustainability of building-scale rainwater harvesting.

In the model, the front page of which is shown in Figure 6 – this is the initial year model, 2007 in this case – enteries are made for a collection area – the roofprint – for the storage – the cistern volume – and for a water usage profile. The model shows how that system would have performed over the modeling period. Again, the goal is to have needed only a limited backup supply, only in the most severe drought years. Covering a rather severe drought period, the results of this model offer a reasonable expectation of water supply coverage by the building-scale system in the future.

Rainwater Harvesting Model

Figure 6

Model runs were conducted for two scenarios: (1) A “standard housing” subdivision, in which the presumed nominal occupancy is 4 persons; (2) A “seniors oriented” subdivision, in which the presumed nominal occupancy is 2 persons. For each scenario, models were run presuming per person usage rates of 45, 40, 35 and 30 gallons per day. 45 gallons/person/day is a usage rate that is expected to not be routinely exceeded by most people in a house with all current state-of-the-art water fixtures, as determined by surveys by the American Water Works Association. 35 gallons/person/day is the commonly assumed usage rate by people who do use rainwater harvesting for their water supply, expecting they would be quite conscious of water conservation. Experience has shown that this usage rate is readily attainable. As is indeed 30 gallons/person/day, based on a number of reports by people who keep track of their water usage.

The modeling outcomes are shown in Figure 7. Based on the expectations of local water suppliers, the coverage that needs to be attained to render the systems “right-sized” would be determined. For this discussion, it is asserted that a coverage of 97.5% or more of total water demand over the 18-year modeling period, leaving no more than 2.5% to be covered by backup supply, would be a “right-sized” system.

Figure 7

On that basis this table shows that for a “standard” subdivision, at a water usage rate of 45 gallons/person/day, a “right-sized” system would need to have a roofprint of 4,000 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 30,000 gallons, as this would provide 97.6% coverage of total water demand through the modeling period. This compares with a 5,000 sq. ft. roofprint and a 42,500-gallon cistern that would have been required to have provided 100% coverage. Following the “right-sizing” strategy, the savings on each house would be 1,000 sq. ft. of roofprint and 12,500 gallons of cistern volume. This would be a rather large savings in costs to build the RWH systems, purchased by using backup supply to cover the last 2.4% of demand, needing backup supply only in the rather severe drought years of 2008-2009 and 2011.

If the water usage rate were 40 gallons/person/day, a full coverage system would require a roofprint of 4,750 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 37,500 gallons. A “right-sized” system providing 98.3% coverage would require a roofprint of 3,750 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 27,500 gallons, a savings of 1,000 sq. ft. of roofprint and 10,000 gallons of storage on each house.

At a water usage rate of 35 gallons/person/day, a full coverage system would require a roofprint of 4,000 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 33,000 gallons. A “right-sized” system providing 97.5% coverage would require a roofprint of 3,000 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 25,000 gallons, again a savings per house of 1,000 sq. ft. of roofprint, and a savings of 8,000 gallons of storage.

A water usage rate of 30 gallons/person/day would require a roofprint of 3,750 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 27,500 gallons to provide 100% coverage. A “right-sized” system providing 98.3% coverage would require a roofprint of 2,750 sq. ft. and a cistern volume of 20,000 gallons, once again a savings of 1,000 sq. ft. of roofprint, and a savings of 7,500 gallons of storage.

Similar observations can be made for the seniors oriented development scenario. All this well illustrates the high value of practicing good water conservation, affording significant savings to build a sustainable RWH system.

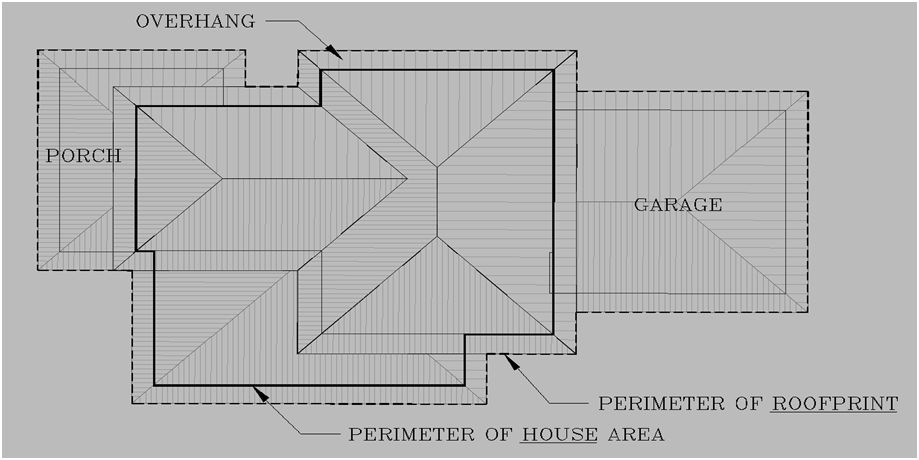

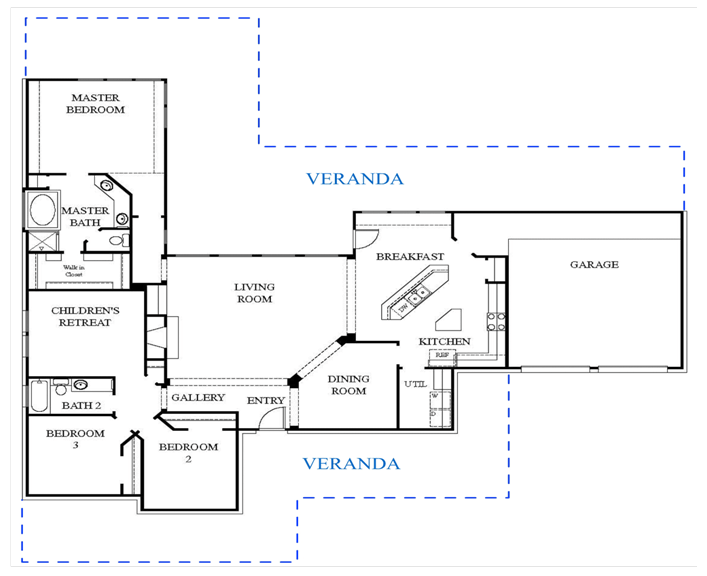

One may look at those roofprints and conclude that the building-scale RWH strategy would only “reasonably” apply to rather high-end developments in which the houses would be “large”. But it is important to understand that the roofprint is not the living space in the house, it is the somewhat larger roof area. As can be seen in Figure 8, this would include in addition to the living area the roof overhangs, the garage (or carport), and covered porches and patios, or verandas. And it is the latter which could readily be expanded somewhat over what might be “normally” built, to provide relatively inexpensive additional roof area to create sustainable systems.

Obviously, single-story houses would be favored, so as to create as much “routine” roofprint as practical. Single-story house plans of several builders active in the Hill Country were examined to see where the addition of verandas could be accommodated, such as is illustrated in Figure 9. It does appear that significant roofprint could readily be added, so that houses with “moderate” areas of living space could have enough roofprint added to obtain the “right-sized” roofprints. Of course, if the house were designed around this idea from the start, these designs could no doubt provide the needed roofprint more cost efficiently, and would yield more attractive designs. So it is suggested that architects and builders consider this, and create “Hill Country vernacular rainwater harvesting house designs”.

In a seniors oriented development, where the nominal occupancy would be 2 persons, a single-story house with a fairly “normal” area of verandas, along with a garage/carport could readily provide the roofprint needed to create “right-sized” systems.

Another advantage to this “veranda strategy” is that the cistern could be integrated into the house design. With a large area of veranda, the cistern need not be very deep under the veranada floor to attain the storage needed. An illustration of building the storage in under the veranda floor is shown in Figure 10.

Of course the cistern could also be built under part of the house too – that has indeed been done in some Hill Country houses – but with this concept, the cistern could be built around the foundation, not impinging on the building itself, so the builder could build rather “normally” within the house envelope. With this strategy, space would not be taken up on the lot for a free-standing cistern. That will be more important on smaller lots, of course.

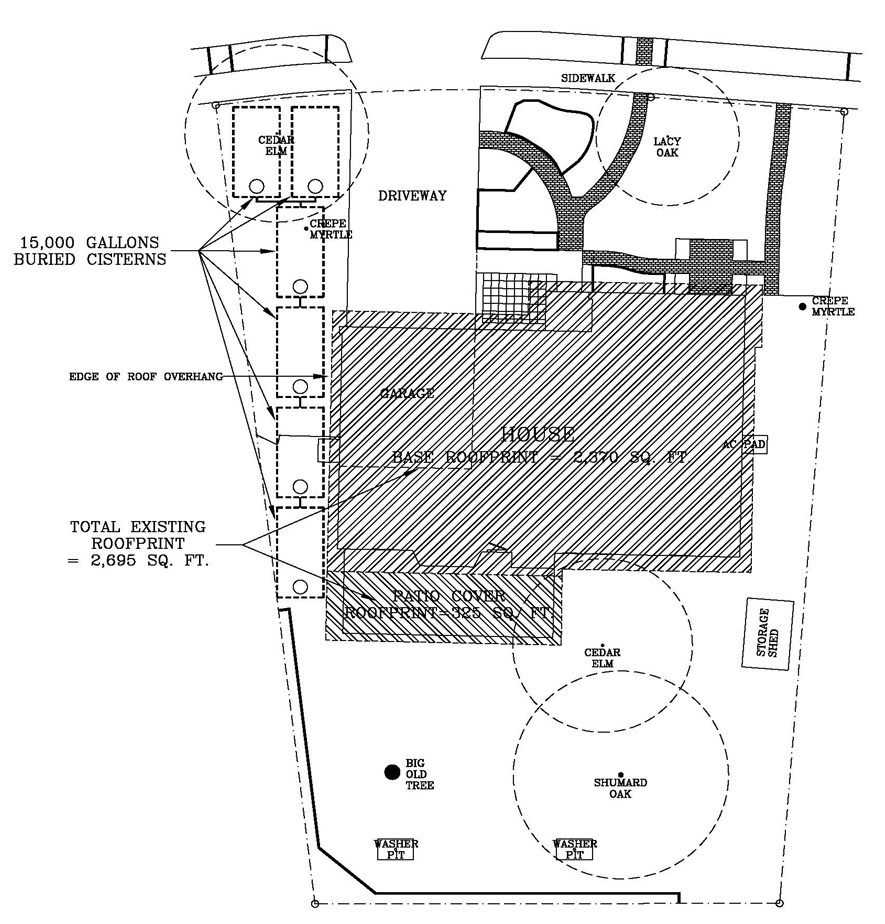

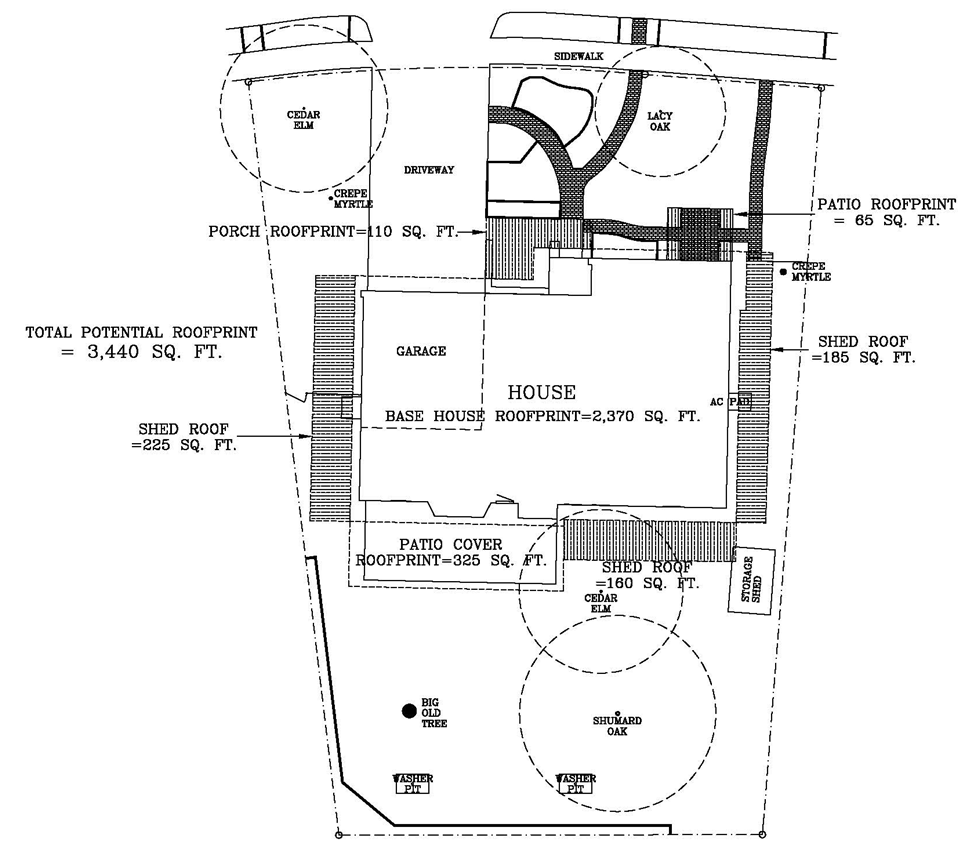

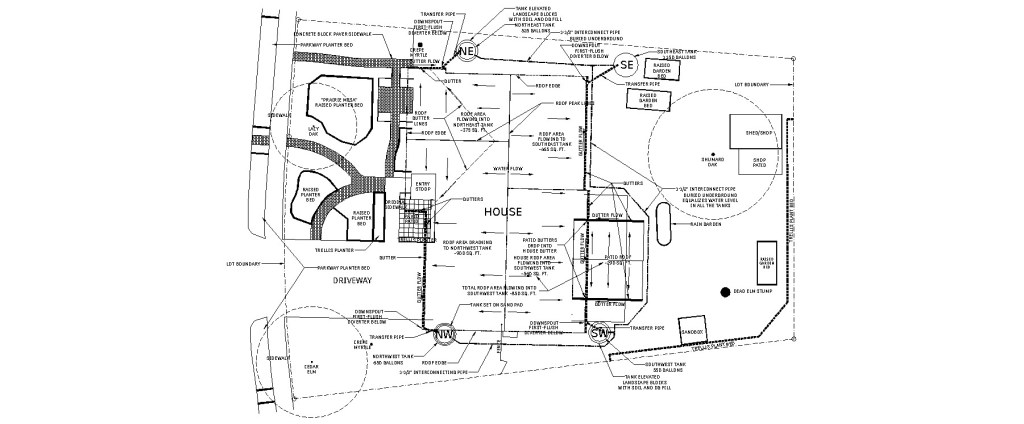

With the roofprint areas needed to “right-size” RWH systems in the Wimberley Valley, it may be questioned if this strategy is indeed only applicable in developments with “large” lots. The example of an urban lot in a South Austin neighborhood offers a look at that. Illustrated in Figure 11, this is a 1/5-acre lot with a 1,580 sq. ft., 3-bedroom, 2-bath house, and a garage, fairly typical in that neighborhood.

Figure 11 illustrates that a system quite sufficient to be “right-sized” for a 2-person household might be accommodated, but would come up somewhat short for a 4-person household. While adding cistern volume might be problematic, as illustrated in Figure 12 roofprint could be added around the house, an adaptation of the veranda strategy noted above, to obtain a roofprint that would be more sustainable for the larger population.

Of course, it is really pretty clumsy to try to retrofit a 1960s era house like this, but if the RWH strategy were to be designed into a new house from the start, it does appear that rainwater harvesting could be a reasonably attainable water supply system on urban-sized lots.

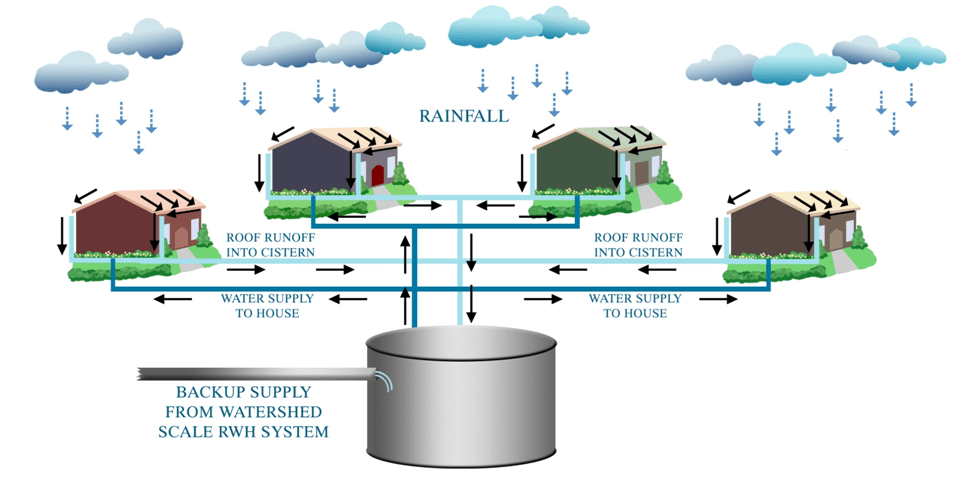

Before moving on, it should be noted that this strategy does not have to be implemented with just individual house RWH systems. As illustrated in Figure 13, to broaden the use of rainwater, RWH could be integrated into the conventional supply with collective, conjunctive use systems, maximizing contribution to water supply from whatever roofprint can be installed. While this scheme would require permitting as a Public Water Supply System, this concept should be entertained, to maximize rainwater harvesting in more intense single-family development, and to extend it to multi-family projects too. Significantly defraying demands on the conventional supply system, and thus blunting the need to expand it with costly, disruptive projects.

5. IRRIGATION WATER SUPPLY FROM WASTEWATER REUSE – CLOSING THE WATER LOOP

Under the Zero Net Water concept, wastewater reuse would be maximized to supply non-potable water demand. Particularly for irrigation in this climate. Indeed, wastewater reuse is highly valuable to rainwater harvesters, if they want to maintain an irrigated landscape. That’s because, as we’ve seen, a “right-sized” system just for interior use is already “large”. So to also supply irrigation directly out of the cistern, the system would have to be made even larger in order to maintain sustainability of the water supply system, and that would be costly, of course. Or the users would have to bring in a MUCH larger backup supply. But neither is needed, as there is already a flow of water sitting right there that could be used for irrigation instead of drawing that water directly from the cistern. A supply for which a hefty price has already been paid to gather. That’s the wastewater flowing from the house. Don’t lose it, reuse it!

An example of the savings potential from using the reclaimed wastewater for irrigation rather than providing that supply directly from the cistern is offered by looking at the 4-person house with a water usage rate of 45 gallons/person/day. The “right-sized” system for supplying just the interior usage requires a 4,000 sq. ft. roofprint with a 30,000-gallon cistern. Per the modeling, that system would have required backup supply in 3 out of the 18 years in the modeling period, totaling 28,000 gallons.

For this illustration, it is presumed the irrigated area to be supplied is 2,400 sq. ft., which would be the nominal size for an on-site wastewater system dispersal field for a 3-bedroom house. If that system were to provide the modeled irrigation demand directly out of the cistern, backup supply would have been needed in 12 of the 18 years, totaling 222,000 gallons! The rainwater system would have covered only 85.6% of total water demand – interior plus irrigation usage – over the modeling period. In order to maintain the sustainability intended to be imparted by the “right-sizing” strategy, the model shows that the roofprint would have had to be increased by 1,500 sq. ft., to 5,500 sq. ft., and the cistern volume increased by 20,000 gallons, to 50,000 gallons. Again, very pricey.

But if the wastewater were reused instead, the system that was “right-sized” to provide only interior use would have also covered most of the irrigation demand by reuse, again having needed backup supply only in the same 3 years, totaling 38,000 gallons. A 10,000 gallon increase in total backup supply from the “base case”, but a far lower demand on the watershed-scale system than if reuse were not practiced.

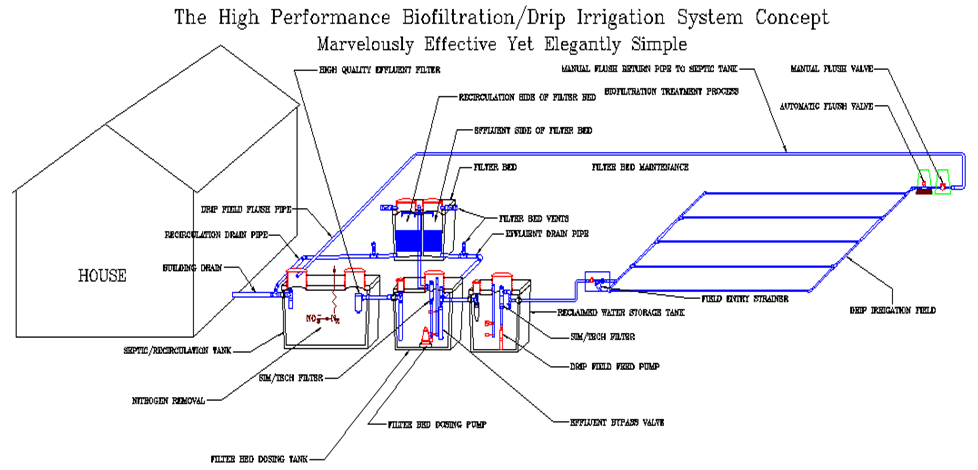

The reuse can be done house by house if the development features larger lots, with wastewater service provided by on-site wastewater systems, commonly called “septic” systems. Those on-site systems can employ the highly stable and reliable High Performance Biofiltration Concept system mated with a subsurface drip irrigation dispersal system. This concept is illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14

This strategy has been implemented in several jurisdictions in Texas, including Hays County, over the last 3 decades. Examples of drip irrigation fields on some of those lots are shown in Figure 15. On-site reuse, to render the RWH systems more sustainable while maintaining grounds beautification, is readily doable in the Wimberley Valley. Indeed, a larger scale version of this system was implemented at the Blue Hole Elementary School, the so-called “One Water” school.

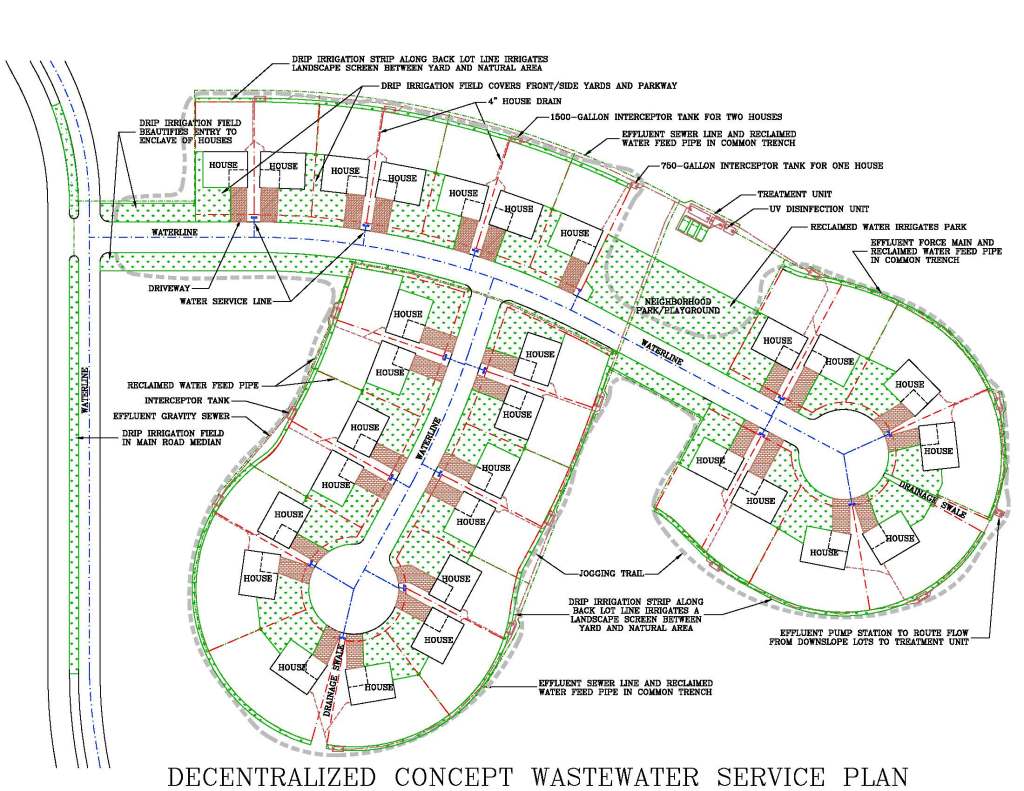

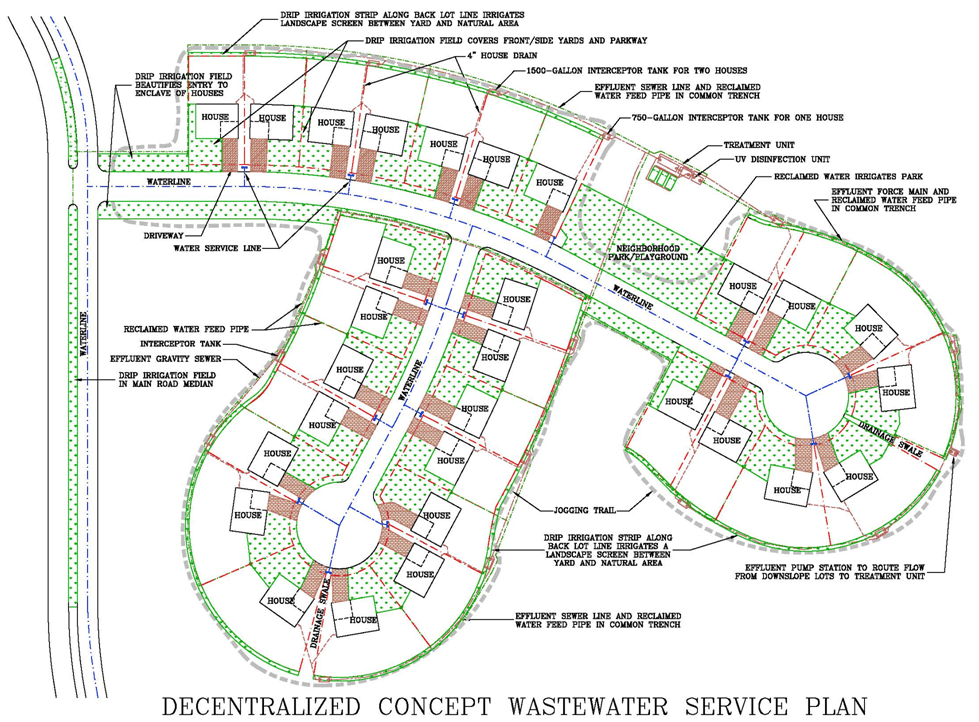

If the nature of the development requires a collective wastewater system – typically needed if a development in the Wimberley Valley has lots smaller than an acre – the reuse can readily be accomplished, rather cost efficiently, with a “decentralized concept” wastewater system. That concept, detailed in “This is how we do it”, is illustrated in the sketch plan in Figure 16, showing a system serving a neighborhood in a rather typical Hill Country residential development. Of course this strategy makes great sense no matter where the water supply comes from. Every development can use this strategy instead of paying the high cost of centralizing wastewater to one far-away location, and then discharging it. Throwing away the water needed for irrigation!

Figure 16

As can be seen in Figure 16, this strategy is about water management, not about “disposal” of a “waste”. Reuse is designed into the very fabric of the development, as if it were a central function, rather than just appended on (maybe) to the system at the end of the pipe, as if it were just an afterthought. And by distributing the system like this, all the large-scale infrastructure outside the neighborhood – the large interceptors and lift stations – would be eliminated, imparting considerable savings.

This highlights that TCEQ must be engaged in rethinking wastewater management, to move to this sort of integrated water management model, instead of viewing wastewater management as being focused on “disposal” of a perceived nuisance. Which makes this wastewater live down to its name, truly wasting this water resource.

6. MINIMUM NET WATER – WORKING THE CONCEPT INTO DEVELOPMENT MORE GENERALLY

Of course if there are conventional water lines already close to a development, the developer would greatly prefer to hook up to them, even if, long-term, very costly measures – like the waterlines some have proposed to run into the Wimberley Valley – would have to be undertaken to keep water flowing to that development. The developer will invariably chose a “normal” water system if it’s available, so the builders can do their normal building designs. Those long-term costs to keep water flowing in those pipes typically accrue to others, so builders and developers wouldn’t see the price signals that might favor a Zero Net Water strategy.

Still a variant of Zero Net Water that might be called “Minimum Net Water” can deliver some of the benefits. If the development will get water service from a watershed-scale system, it can still be arranged to pretty much take irrigation off that potable supply, by rainwater harvesting and/or wastewater reuse. In this region, that would typically lop off about 40% of total annual demand. And of course it would be an even higher percentage of peak period demand, and it is peak demand that drives a lot of water system investment, so that is very valuable.

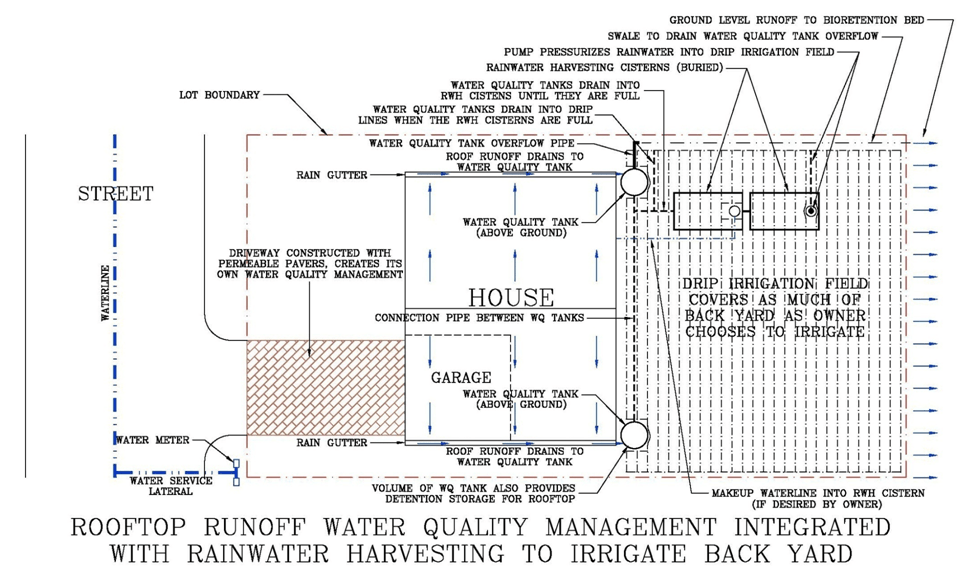

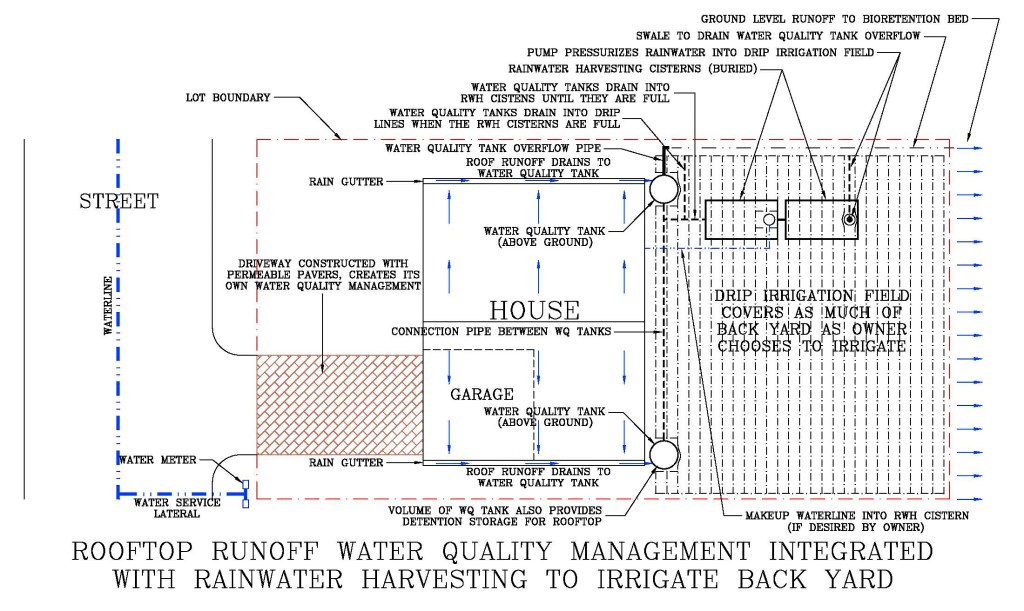

This could be done with a combination of the neighborhood-scale wastewater reclamation system, illustrated above, using that water to irrigate the public areas – front yards, parkways, parks and such – and rainwater harvesting to irrigate the private spaces, the back yards. Under this scheme, roof runoff would collect in “water quality” tanks, as shown in the illustration in Figure 17. That part of it conforms to what Austin sets forth in its rules as “rainwater harvesting” for water quality control, under which these tanks would have to drain within 48 to 72 hours. In this scheme, however, these tanks would be connected to rainwater harvesting cisterns, where that water could be held until whenever it is needed to irrigate the back yard. And only when those cisterns were full would any water even pond up in the water quality tanks, to eventually flow “away”. So a lot of the roof runoff would be harvested, to be used for irrigation, instead of running “away”.

By taking care of water quality management of rooftop runoff like this, the green infrastructure needed to treat runoff from the rest of the site could be downsized. Bioretention beds would need to be sized only for the area and the impervious cover level obtained by omitting all the rooftops. That saves more money, while still well maintaining the hydrologic integrity of the site.

The bottom line is water quality management of this rooftop runoff would be integrated with rainwater harvesting to create an irrigation water supply. Doing this would impart superior water quality management of that runoff, restoring the hydrologic integrity of this patch of ground now covered with the rooftop, and providing irrigation water for the back yard. A lot of benefit obtained by a pretty simple, straightforward system.

7. COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT, A PRIME OPPORTUNITY

To this point, the Zero Net Water strategies have mainly been focused on housing developments, but commercial and institutional buildings are also a major opportunity for Zero Net Water. The ratio of roofprint to water use in those buildings typically favors rainwater harvesting. And condensate capture could also provide a significant water supply in this climate.

Along with RWH providing the original water supply, project-scale wastewater reuse could be employed for irrigation, and also for toilet flush supply, and the LID/green infrastructure stormwater management scheme could harvest runoff from paved areas of the site too, and feed it into landscape elements – rain gardens – that, again, don’t need routine irrigation. An illustration of applying these strategies to a commercial building is shown in Figure 18.

Using these strategies, commercial and institutional buildings, or whole campuses of these buildings, could readily be water-independent – “off-grid”, not drawing any water from the conventional water system. That could save a lot of water, and a lot of money for conventional water and wastewater infrastructure that would not have to be built to these projects.

8. COSTS … AND VALUE, A CLOSING STATEMENT

And finally, about cost. Of course, that’s always going to be a major factor in whether any of these strategies are put to work in service of society, to deliver water systems that are more societally responsible and more environmentally benign. But it is suggested that the discussion be framed in terms of VALUE. Oscar Wilde famously said, this society knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. That just might be the case here.

Because, by conventional accounting, water supply obtained from building-scale rainwater harvesting will no doubt appear quite expensive per unit of yield, mainly because of the high relative cost of cisterns, the distributed reservoir. A viewpoint exacerbated by presuming the watershed-scale storage and distribution systems are sunk costs, rather than the avoided costs they would be – or at least expansions of them would be – if building-scale systems were used instead of the watershed-scale system for whole developments. So mainstream institutions tend to dismiss this strategy out of hand. Indeed, the State Water Plan assigns little value to building-scale rainwater harvesting as a water supply strategy, and water suppliers in this region appear not to consider it to be any part of their portfolios.

But there are many reasons to consider if the Zero Net Water strategy delivers value that should not be ignored. Here are a few of them, very briefly, as each of these could be a day-long discussion themselves:

- The Zero Net Water strategy minimizes depletion of local groundwater and loss of springflow. That is very important in places like the Wimberley Valley, indeed in much of the Hill Country. As the aquifers to the east of the IH-35 corridor are dewatered by importing that water into Hays County, Zero Net Water could be valuable over much of that area as well.

- That’s because Zero Net Water would blunt the “need” to draw down aquifers, or take land to build reservoirs, and all their attendant societal issues. An example is the brewing water war in East Texas, where it is proposed to take land to build reservoirs and export groundwater out of that area as well.

- As has been noted, Zero Net Water will be sustainable over the long term, since development would largely live on the water that’s falling on it, not by depleting water that’s been stored in aquifers over centuries, or getting it from reservoirs that will silt up.

- Zero Net Water is an economically efficient strategy, since facilities are built, and paid for, only to provide water supply that is imminently needed.

- Zero Net Water also minimizes public risk. Since the system is designed into the site as it is developed, the cost of creating water supply is largely borne by those who benefit directly from that development, rather than by society at large through public debt.

- It must be understood that growth projections for this region are not manifest destiny. While large water infrastructure projects just have this, if you build it, they will come, sort of “justification”, those growth projections depend on a continuation of trends the projections are based on. And that might be disrupted by any number of circumstances. So perhaps it should be asked, what if they built it and no one came? Or just, not enough to pay for it came? Perhaps the projected growth is indeed inevitable, and so that’s a remote risk, but still it’s one that could be avoided by shifting to Zero Net Water.

Zero Net Water is about society collectively saying, this is how we will secure our water supply. We will integrate all aspects of water management, we will address all water as a resource, we will tighten up the water loops and maximize efficiency, to create a sustainable water strategy – Zero Net Water.