The Waterblogue has featured the idea that building-scale rainwater harvesting (RWH) can provide a significant contribution to water supplies in this region. For example here, here, and here. Raising the obvious question, what actual contribution could this strategy make?

Discussing the merit of and prospects for building-scale RWH as a water supply strategy in this region with a colleague, I was surprised when he confronted me with this proposition. According to state policy, in order to be considered a functional water supply strategy, a method must be capable of delivering a “firm yield” through a repeat of the “drought of record”, and under that definition, most building-scale RWH systems simply do not exist, do not deliver any recognized water supply!

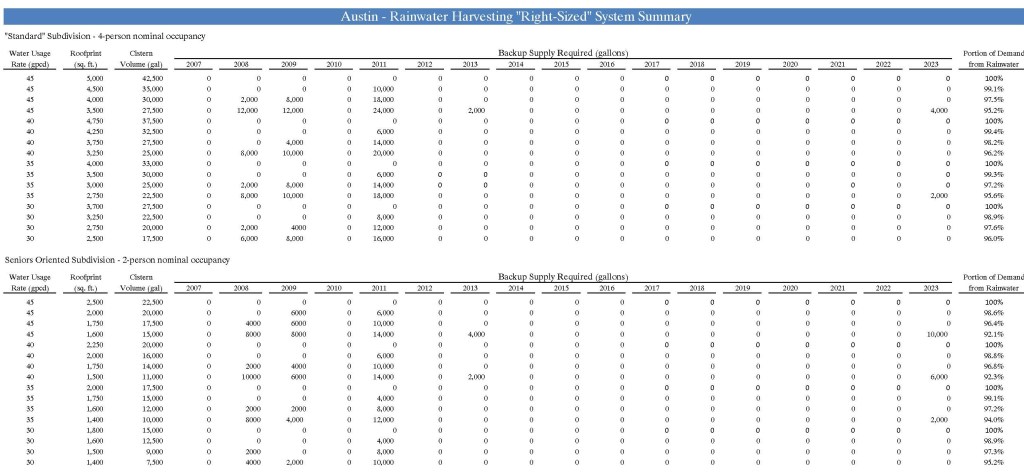

Let that sink in for a moment. A well-planned, well designed building-scale RWH system around here is typically expected to be able to provide in excess of 95% of total demand over a period of years, which would include a period of drought. An example is the “right-sized” system summary shown below produced by modeling the period 2007-2023, inputting Austin rainfall records over that period. This time period includes 2008-2014, which is reported to be the new “drought of record” period for the Highland Lakes, which is the major watershed-scale RWH system that serves this region.

As you see, we can readily choose system sizing relative to the expected level of water usage to create systems that can indeed deliver 95% or more of the total water supply over the modeling period. So to the question, if the system does not deliver the total water supply needed through a drought period, what would it take to assure this strategy does deliver a functional, secure and assured water supply?

I posed this matter in the TWDB-funded investigation “Rainwater Harvesting as a Development-Wide Water Supply Strategy” that I ran for the Meadows Center at Texas State University in 2011-2012. I set forth the idea of “right-sizing”, that rather than having to pay to upsize the RWH system to cover the last little bit of demand, it would be more cost efficient society wide to install a “right-sized” system that would provide the vast majority of total water demand, and to provide for a backup supply of the small amount of shortfall, that would be needed only though bad drought periods. As can be seen in the table above, for example, to provide 100% supply at 45 gallons/day to a 4-person household would require 5,000 sq. ft. of roofprint and a 42,500-gallon cistern. But that system could be downsized considerably, to 4,000 sq. ft. of roofprint with a 30,000-gallon cistern – saving a ton of money – and would still have provided 97.5% of total demand through the modeling period. So the question becomes, how to assure that 2.5% shortfall could be provided by other means.

The presumption behind this concept is that there is not an unlimited market for development. The development that would be provided water supply by building-scale RWH systems would displace development that would have otherwise drawn its water supply from the watershed-scale RWH system, rather than be development in addition to that. So the supply being provided by building-scale RWH would be supply that would be left in the watershed-scale system storage pool most of the time, so presumably not drawing it down as severely as it would have been if all those building-scale systems had instead been routinely supplied by the watershed-scale system. Thus the watershed-scale system would have the “slack” to provide the relatively small amount of backup supply to the building-scale systems through the drought periods.

In the example above, “right-sizing” at 4,000 sq. ft. and 30,000 gallons, the table shows a total backup supply of 28,000 gallons would have been needed through the drought period 2008-2014, or just 4,000 gallons per year on average, out of a total modeled demand of 65,700 gallons/year. That system would have been 94% supplied by the building-scale RWH system through that 7-year drought period, and as noted above 97.5% supplied through the total 17-year modeling period.

The question, of course, is if indeed the watershed-scale RWH systems – such as the Highland Lakes in this area – would have the capacity to provide that backup supply demand through a drought period, as well as continuing to serve all the development that routinely draws from it. My colleague, while acknowledging the logic of my argument, asserted that the “growth model” presumes that the watershed-scale systems serving any given area would indeed become completely encumbered by development they serve directly – based I’m guessing on the very circumstance that overall growth around here is projected to exceed the capacity of existing water supplies to service it – so that it’s presumed there would be NO capacity available in that system through a drought of record period.

As best I can translate, it is asserted that the “right-sizing” strategy is illegitimate, because there would be no sources available for backup supply through a drought. So rendering that evaluation noted above, that if the building-scale system would not carry 100% of the projected supply needs, for the purpose of planning water supply strategy, it is presumed that the system provides NO water supply, is of NO value to the regional water economy.

I find that viewpoint to be, well, strange, contrary to common sense. Does it not seem that if a building-scale system provides in excess of 95% of the total supply over a period of years, that would be supply that the watershed-scale system is relieved of having to provide, and so this is effective water resource conservation, that does have value to the regional water economy? It seems rather didactic to simply “erase” the whole building-scale RWH water supply strategy because it would need a minor portion of total supply to be provided out the watershed-scale system, which the building-scale systems would be totally relieving much of the time. Indeed, one wonders where else in public policy is a 95+% “success” rate deemed “unreliable”? Yet that is what my colleague contends state planning principles presume “must” be so when considering whether to base water supply strategy on any use of building-scale RWH over any given area. That only the capacity of systems sized to deliver 100% of the projected supply can be deemed to exist.

It is little wonder then that we do not see the building-scale RWH strategy being set forth in any of the regional water plans, and thus not having been meaningfully incorporated into the State Water Plan. Here is the sum total of what the 2022 Texas State Water Plan says about building-scale RWH as a water supply strategy:

“Rainwater harvesting involves capturing, diverting, and storing rainwater for landscape irrigation, drinking and domestic use, aquifer recharge, and stormwater abatement. Rainwater harvesting can reduce municipal outdoor irrigation demand on potable systems. Building-scale level of rainwater harvesting, as was generally considered by planning groups and which meets planning rules, requires active management by each system owner to economically develop it to a scale that is large and productive enough to ensure a meaningful supply sustainable through a drought of record. About 5,000 acre-feet per year of supply from rainwater harvesting strategies is recommended in 2070 to address needs for select water users that have multiple additional recommended strategies.”

To put that projection of supply to be provided by building-scale RWH in perspective, if we presume a typical system does provide supply at 45 gallons/person/day for 4 persons, or 180 gallons/day total, each such system would supply 65,700 gallons/year, or about 0.2 acre-feet/year. So a contribution of 5,000 acre-feet/year would require 5000/0.2 = 25,000 RWH systems of this size, or the functional equivalent, to be put in place. How much growth of this strategy does this project?

While there is no authoritative data base that would provide the number of existing RWH systems, a rough guess that one expert on the subject offered is that there is likely in excess of a quarter million RWH systems – 10 times the number calculated above – in just 7 states, with Texas being the site of a goodly portion of those. Indicating that it does not appear the 5,000 acre-feet by 2070 projection even comes close to representing what is already on the ground, routinely producing water supply today.

But, as reviewed above, those who set water planning policy in Texas are loathe to accord to this strategy any actual contribution to supply, because of that “firm yield” requirement. So we need to consider if that is indeed sound reasoning, if that is a sufficient reason to exclude all contributions by building-scale RWH systems all of the time, or if we should rethink that.

Might, for example, society be better served by planning for building-scale RWH systems within a “conjunctive use” strategy, under which whatever the backup supply source is would have that capacity “reserved” in some manner? Just as this concept is applied to co-managing surface water and groundwater, so that one source might “fill in the gaps” of the other source’s capacity. To do this of course would require conscious consideration of and planning for building-scale RWH as a contribution to area-wide water supply. Which is absent at present, and so this matter remains “fallow”.

There are hundreds if not thousands of houses, businesses too, around here where folks are making building-scale RWH work as a water supply strategy, successfully arranging for whatever backup supply their systems need on an ad hoc basis. All of the water hauling companies that provide that backup supply report they are confident their business model will remain viable, so those supplies can be maintained into the future. So it would seem that building-scale RWH could indeed be a broad scale water supply strategy, with some intentional planning for assuring backup supplies are provided at need.

The situation can be summed up, that building-scale RWH is not meaningfully included in water resources planning in Texas, upon the “reasoning” that this method would not provide a “firm yield” through a repeat of the “drought of record”. This ignores any prospect for co-managing this strategy with the watershed-scale RWH systems to assure that whatever gaps in firm yield would result would be covered out of the watershed-scale systems. Does this not seem to show a lack of vision among the mainstreamers who control those planning processes?

In pursuit of society’s best interests, it is suggested that this whole viewpoint be revisited. This is another example of how we need to take a peek down the road not taken … so far. As that could make all the difference.