I am part of a group that is putting together a course, perhaps to be offered by Texas A&M, to teach the “One Water” concept, culminating with a “certificate” that is expected to have some meaning for practice in this arena. The major activity in the first gathering of that group was to set forth ideas on what the course content should cover. As a “conversation starter” I offered the group a rundown on what the “components” of a “One Water” scheme might include. A major theme of that document was that “One Water” schemes would be basically “distributed” concepts. Let’s explore that whole idea.

A working definition of “One Water” is offered by the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University as:

“One Water is an intentionally integrated approach to water that promotes the management of all water – drinking water, wastewater, stormwater, greywater – as a single resource.” [emphasis added]

This definition can be illustrated in practice by these examples:

- Wastewater and water supply can be integrated by designing and developing the “waste” water system to focus effort and resources on producing a reclaimed water supply, preferably close to the point of reuse, which would be utilized to defray demands on the “original” water supply to the project.

- Stormwater management and water supply can be integrated by capturing the additional runoff caused by development, in cisterns and/or landforms, rather than allowing it to “efficiently” drain “away”, with the captured water used as explicit water supply – e.g., building-scale rainwater harvesting, using water captured from roof runoff into cisterns to defray, or displace, demands on the “original” water supply – or to enhance the hydrologic integrity of the site by maintaining the rainfall-runoff characteristics of the “native” site on the developed site, holding water on the land instead of “desertifying” the land by draining “away” water that would have otherwise infiltrated to maintain deep soil moisture, to recharge aquifers, etc.

These examples highlight a fundamental imperative of “One Water” practice – to maximize the sustainability of water supplies, these integrated management strategies must focus on addressing all water as a resource to be husbanded, not as a “nuisance” to be gotten rid of, to be wasted as expeditiously as possible, which has been the focus of conventional stormwater and wastewater management practice. Of course, the water does not actually “go away” – the hydrologic cycle is a closed system on a global scale – but those practices are wasteful in that they expend resources to route the water out of, rather than to maximize its beneficial use within, the immediate environs. Each gallon that is so externalized (wasted) is another gallon that must be imported into the project, and (in this region particularly), all existing water supplies are becoming increasingly strained.

A basic principle, highlighted for example by Paul Brown of CDM – a voice from the very heart of the mainstream – in his preface to Cities of the Future, is that water is most sustainably managed by maximizing the beneficial use of these resources within the project, as much as practical, “tightening up” the loops of the hydrologic cycle, rather than externalizing those resources and then importing water from “traditional” supplies to make up for these externalized – wasted – resources. By following this “One Water” practice, the developer, the eventual users of the project, and the community-at-large will realize fiscal, societal, and environmental benefits.

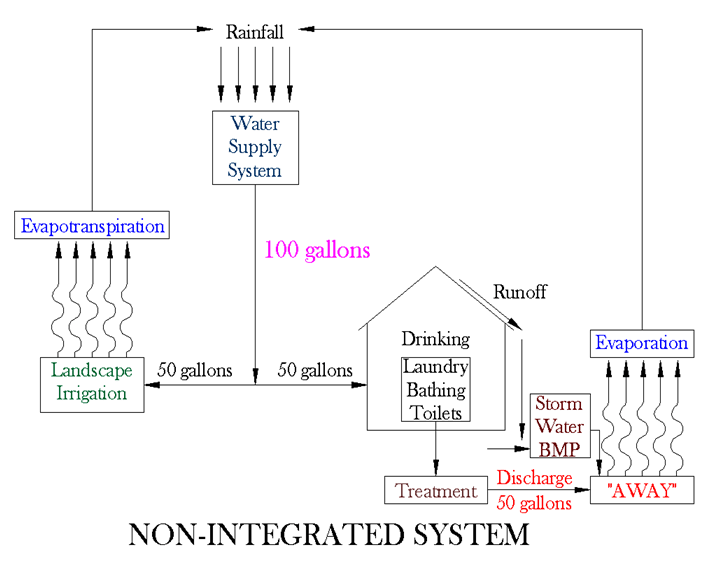

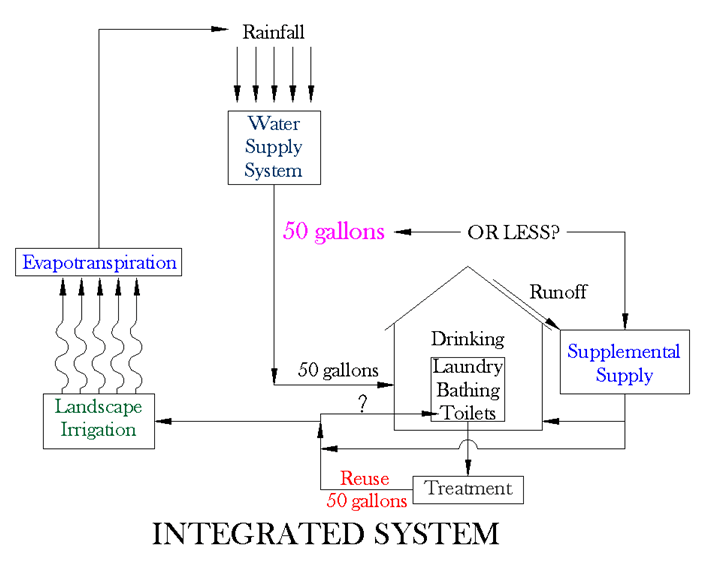

A simple schematic comparing a non-integrated – or “silo’d” – system with an integrated management system is shown in the figures below, illustrating how husbanding of the water resource may be enhanced by this “tightening” of the water loops. As this illustrates, the same overall function might be obtained while imparting about one-half the draw on the “original” water supply to a project.

As this illustrates, the “One Water” methods would integrate into the land plan, rather than being appended on, divorced from the land plan, as is typical under the “silo’d” conventional management strategies. In short, water resources sustainability would be designed into the very fabric of each project. And thus, we see that “One Water” would typically be most effectively accomplished by decentralizing the water resources management infrastructure.

Before proceeding, it is important to acknowledge that context is important, and in each circumstance, the full range of available options should always be evaluated, including both “centralized” and “decentralized” schemes. So while it is presented here that distributed infrastructure seems typically more likely to produce the better “One Water” schemes, there will of course be instances in which a more conventional looking “centralized” infrastructure would prove to be the “better” option. For example, in an area with the conventional centralized “waste” water system architecture already in place, the “best” option for assuring that “waste” water realizes its resource value may be the installation of a “purple pipe” system to redistribute water from the centralized treatment plant to points of reuse.

Moving on … While as noted the intention should always be to integrate the various water management functions, in practice each of them – water supply, “waste” water management, and storm water management – are typically addressed individually, with the “integrations” generally falling out of the means and methods that are utilized. Referring to the examples listed above, water supply and “waste” water management could be integrated by utilizing the “waste” water resource to defray demands on the “original” water supply source for the project being served by that “waste” water system. Note that the water supply system itself would not be “perturbed” by this scheme, it’s just that part of the supply would now be shunted off to the “waste” water being reused to create that adjunct supply.

Generally, as also noted above, that integration, the defraying of water supply demand, would be maximized by designing that whole process into the very fabric of the development. Which brings us to the “decentralized concept” of “waste” water management.

Noting that the “One Water” concept generally entails “tightening” the water loops, integrating water management into the very fabric of development, it becomes rather obvious that “waste” water systems would be “distributed”, rather than “regionalized”, as is the mantra of much of conventional practice. The “decentralized concept of ‘waste’ water management” – set forth quite consistently by the author over the last 37 years – embodies this whole idea. This is an alternative organizing paradigm for a “waste” water system of any overall scale. Here is the basic idea, as set forth in a 1988 paper by the author:

“Stated simply, the decentralized concept holds that ‘waste’ water should be treated—and the effluent reused, if possible—as close to its source of generation as practical. In particular, it is suggested that the first stage of treatment—for which a septic tank is preferred, as outlined later—be placed at or very near to the ‘waste’ water source, regardless of how centralized the rest of the system is. The conventional “on-site” system might be viewed as the ultimate embodiment of this concept, and on-site systems might indeed be the appropriate technology for parts of the service area. In areas where soil and/or site conditions dictate that conventional on-site systems would not be environmentally sound, the septic tank effluent might be routed through further treatment processes before dispersal or reuse.

“However, the concept is very “elastic”. In practice, it may be beneficial to aggregate several waste generators into one septic tank or to route septic tank effluent from several generators into a collective treatment and dispersal system. The most appropriate level of aggregation at any stage of treatment would be determined by a number of considerations, such as topography, development density, type of land use, points of potential reuse, or locations where discharge is allowable.

“Judicious choice of technology at each stage of the collection and treatment system can help advance fiscal, societal and environmental goals.”

Note in particular three items in that description:

- The term “waste” is in quotes to highlight that “wastewater” is a complete misnomer for designating what, within a “One Water” concept, must be addressed as a water resource to the maximum extent practical in each circumstance.

- The over-arching aim of “wastewater” management is not “disposal” – as basically defines conventional practice – rather must be focused on producing a reclaimed water, to be used to defray demands on the “original” water supply to the project being served by the “waste” water system, to the maximum practical extent in the circumstances at hand.

- With the overall system distributed, practical operation of multiple distributed treatment units demands that “judicious choice” of technologies to be used to assemble the system.

This all leads to identifying the basic “tools” of the decentralized concept, as has been set forth by the author and others in any number of works in this field, those tools being:

- Effluent sewerage is highly favored for any collection of “waste” water beyond the building site level. This is the concept of intercepting flows at, or very near to, the site of their generation in septic tanks – termed “interceptor tanks” within the effluent sewerage concept because they intercept the “big chunks”, leaving only liquid effluent with very low levels of settleable solids to be transported any further, so allowing the use of effluent sewers, instead of conventional “big pipe” sewers. This reduces the cost of the “remant” collection system that remains in the distributed system and minimizes the environmental impacts of the collection system, practically eliminating leaks, bypasses and overflows, not to mention minimizing the degree of disruption entailed in installing the smaller, shallower effluent sewer collection lines.

- Treatment beyond the septic tank must be done with “fail-safe” technologies. The term “fail-safe” is in quotes because any sort of treatment unit must be properly operated and maintained so as to continuously and reliably produce the expected effluent quality, but certain technologies, by dint of their very nature, are more robust and “forgiving”, and so can stay “on track” with rather minimal O&M effort and attention. This is essential to creating a management system that would not become overtaxed by needing to police the multiple treatment centers that following the decentralized concept would create. What types of treatment units that fall into the “fail-safe” category, and how to design those units will likely be a matter of opinion in this field. It is the author’s long-held view that inherently stable technologies like the recirculating packed-bed filter and constructed wetlands be highly preferred in lieu of the activated sludge process that is practically the “knee-jerk” choice in conventional practice. This is because the activated sludge technology is inherently unstable, an effect that becomes more problematic in “smaller” treatment plants, really anything but the treatment plant being “based loaded”, as is extant only in large “regional” treatment plants.

- Again, the fate of the effluent, the reclaimed water, is to serve water uses that would need to be met whether or not the effluent were available for that usage, and to properly apply the reclaimed water to serve those demands, and so defray demands on the “original” water supply source. It is to be expected that irrigation is likely the most “available” and readily served use in many cases. In particular in climates such as exist in this region, for which subsurface drip irrigation – itself a “fail-safe” technology of sorts – should be preferred, to maximize irrigation efficiency – also of course a basic “One Water” principle” – and to sequester the reclaimed water underground to minimize potential for human contact in the highly distributed reuse sites. Other uses may include toilet flushwater supply, cooling tower blowdown makeup, and perhaps even laundry water supply.

An example of how these tools could be employed to create a decentralized concept system strategy was reviewed in “This is how we do it”, showing the benefits, in particular to practically maximize the resource value of the “waste” water, of the decentralized concept scheme vs. a conventional development-scale system or a conventional centralized system.

Thus we see that in terms of “waste” water management, “One Water” basically equals the “decentralized concept” of “waste” water management. This strategy focuses investments on properly treating and effectively reusing the water resource, rather than on just moving the stuff around – which is all the far-flung collection system within the conventional centralized system architecture does – by eliminating most of that collection system. Employing creative system concepts and more “fail-safe” technologies, this scheme also makes the overall system cost effective to operate, and blunts environmental impacts inherent in “waste” water management.

Under a “One Water” strategy, water supply and storm water management would also be generally more distributed systems than they are under conventional practice.

The “traditional” view of storm water management centers on “efficient” drainage “away” from the development of increased runoff imparted by development, so as not to impart nuisance flooding of project grounds, and to assure that as this water flows “away”, it does not create downstream problems, either due to streambank erosion or overbank flooding. This “efficient drainage” viewpoint often results in whatever constructions used to attain those aims being “end-of-pipe”, essentially appended onto the project, rather than distributed facilities designed into the very fabric of the development.

An essential “One Water” strategy is to “retain, not drain” the runoff, at least up to the point that this water would have infiltrated rather than flowed “away” from the “native” site. The aim is to maintain as much as practical the “hydrologic integrity” of the site – that is, to maintain the rainfall-runoff response as similar to that of the “native” site as practical – and by treating multiple sites in a watershed in this manner, to maintain rather than degrade the hydrologic integrity of the watershed.

The means by which this would be accomplished would be implementing the “low-impact development” (LID) concept, imparting rainwater harvesting – either “formally” in cisterns or by capturing runoff in specialized landforms generally termed “green stormwater infrastructure” – on a highly distributed basis. Again, designed into rather than appended onto the development. When I first learned of LID, it immediately hit me that this is basically a “decentralized concept of storm water management”. So here too, “One Water” = the “Decentralized Concept”.

An example of this sort of distributed LID concept was illustrated in “… and Stormwater Too”, showing how rainwater harvesting from rooftops, permeable pavement, and rain gardens (bioretention beds) would create a highly efficient scheme to both hold more water on the land and to utilize the rooftop runoff to further defray landscape irrigation demands.

Another example is applying this concept to a big-box store parking lot, as is illustrated here. This shows how to indeed maintain, or better, the rainfall-runoff response of the “native” site, while providing water quality treatment just as a matter of course as the water flows through the site.

Regarding water supply, not only would building-scale rainwater harvesting (RWH) typically be a component of the storm water management scheme – so potentially creating a supply that could be used to defray water demands rather than just being drained “away” after being detained in the cistern – but some, even all, of the water supply strategy could be based on building-scale RWH. This all plays into what I have termed the Zero Net Water concept.

True to its name, Zero Net Water is a water management strategy that would result in zero demand on our conventional water supplies – rivers, reservoirs and aquifers. Under the Zero Net Water development concept, water supply is centered on building-scale rainwater harvesting, “waste” water management centers on project-scale reclamation and reuse, and stormwater management employs distributed green infrastructure to maintain the hydrologic integrity of the site. So basically it’s really another name for “One Water”. Together these result in minimal disruption of flows through a watershed even as water is harvested at the site scale and used – and reused – to support development there. In the general case, this concept might be approached – you might call it “minimum net water” – to defray but not eliminate demands on the conventional water supply sources.

Our conventional supply systems are watershed-scale rainwater harvesting systems, utilizing reservoirs, aquifers and streams as the “cisterns” to hold the water supplies awaiting various uses. Noting that an essential water use is maintenance of environmental integrity – e.g., maintaining aquifer levels so as not to reduce spring flows, keeping enough flow in streams to service various environmental functions, including delivery of water into bays and estuaries to maintain those ecologies. So we need to be saving as much water as we reasonably can, and minimizing disruption of flow through the watershed. The “minimum net water” approach would serve that end.

While it will not be belabored here, distributing the water supply system to the building scale creates an inherently more efficient system, as it eliminates transmission losses and evaporation losses from reservoirs, and it requires less energy, as the water needs to be moved only short distances, with small elevation heads. It would also be more economically efficient, as the water supply would be “grown” – thus paid for – in fairly direct proportion to water demand, one building at a time.

In closing, a more recent focus of “One Water” practice is the capture of air conditioner (AC) condensate, applying the water so captured to providing water supply, to defray demands on the “original” water supply source to the site. Clearly, condensate capture would also be a very highly distributed strategy, executed at the building or campus scale.

So it is that not only does “One Water” = the “Decentralized Concept” in the “waste” water management arena, “One Water” would optimally be a rather highly distributed strategy for water supply and storm water management as well. Moving from the conventional centralized “waste” water system architecture to the decentralized concept strategy has been a challenge for the mainstream of this field. Over the almost 4 decades I’ve been advocating for that paradigm shift, very little movement has been seen on that front. It is to be expected that moving off “end-of-pipe” management to a highly distributed LID strategy, and integrating building-scale RWH into the water supply strategy on a broad scale will be similarly challenging to the field, as these moves also require a paradigm shift.

Despite the “One Water” concept having been “a thing” in this field for many years now, despite years of “happy talk” around moving society toward a “One Water future” and such, we have seen precious little of all this hitting the ground. To the extent that, when a local environmental activist queried the U.S. Water Alliance – a major “cheerleader” for “One Water” – on examples where “total One Water” schemes, entailing all the water management functions, could be found, the response was … [crickets chirping]. One wonders, how much is that lack of movement in practice due to the paradigm shift to more decentralized schemes not having taken hold in the water resources management field? Indeed, we have a lot more work to do before it will become broadly recognized that “One Water” = the “Decentralized Concept”. But until that happens, it’s highly likely the movement toward “One Water” will continue to be very slow.

Or so is my view on this matter. What’s your view?